Why Didn't Coronavirus Tracing on Android & iOS Work?

Digital contact tracing on iOS and Android was a flop. Despite heroic efforts by passionate engineers, public health leaders, and epidemiologists around the world, I speculate that the total cumulative benefit from automated digital contact tracing on iOS and Android has been close to zero. I think there are a few clear reasons why it flopped, and what we’ll need to do differently in the next pandemic. (Disclaimer: although I work for Google, I wasn’t involved with this in any way, and am writing about this more as a case study in product management.)

What should success have looked like?

If humanity had pulled this off, we’d have a global, unified system that anonymously and securely notified three billion people if they were recently exposed to someone who has covid. By being automated and fast, we could stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2 by immediately informing the exposed but not yet symptomatic, so they could quarantine, lowering disease spread while still enabling a semblance of normal life to continue for those who didn’t get alerted. And because Android and iOS span the world, the system can effortlessly span borders.

But we didn’t get that for this pandemic, and it’s entirely possible if we don’t cure the things that went wrong, we won’t have it for the next one either. I think things went wrong in three big places:

- Google and Apple’s key product decisions

- Fragmented governmental responses, especially visible to me as U.S. resident

- Weak public adoption & interest

Google & Apple were too timid to own the whole solution

The default setting needed to be “coronavirus exposure tracking is on.” If a global pandemic killing millions isn’t the time to switch people’s default expectations, when is it going to be enough? The ideal experience here should have been an OS update that immediately informed you that coronavirus exposure tracking was now enabled, and instructions on how to disable it. Leaving it turned off by default, and requiring people to go into the app store, find the relevant local app they needed to download and install, and then enable it, was far too high of a barrier to get sufficient usage to make a big difference.

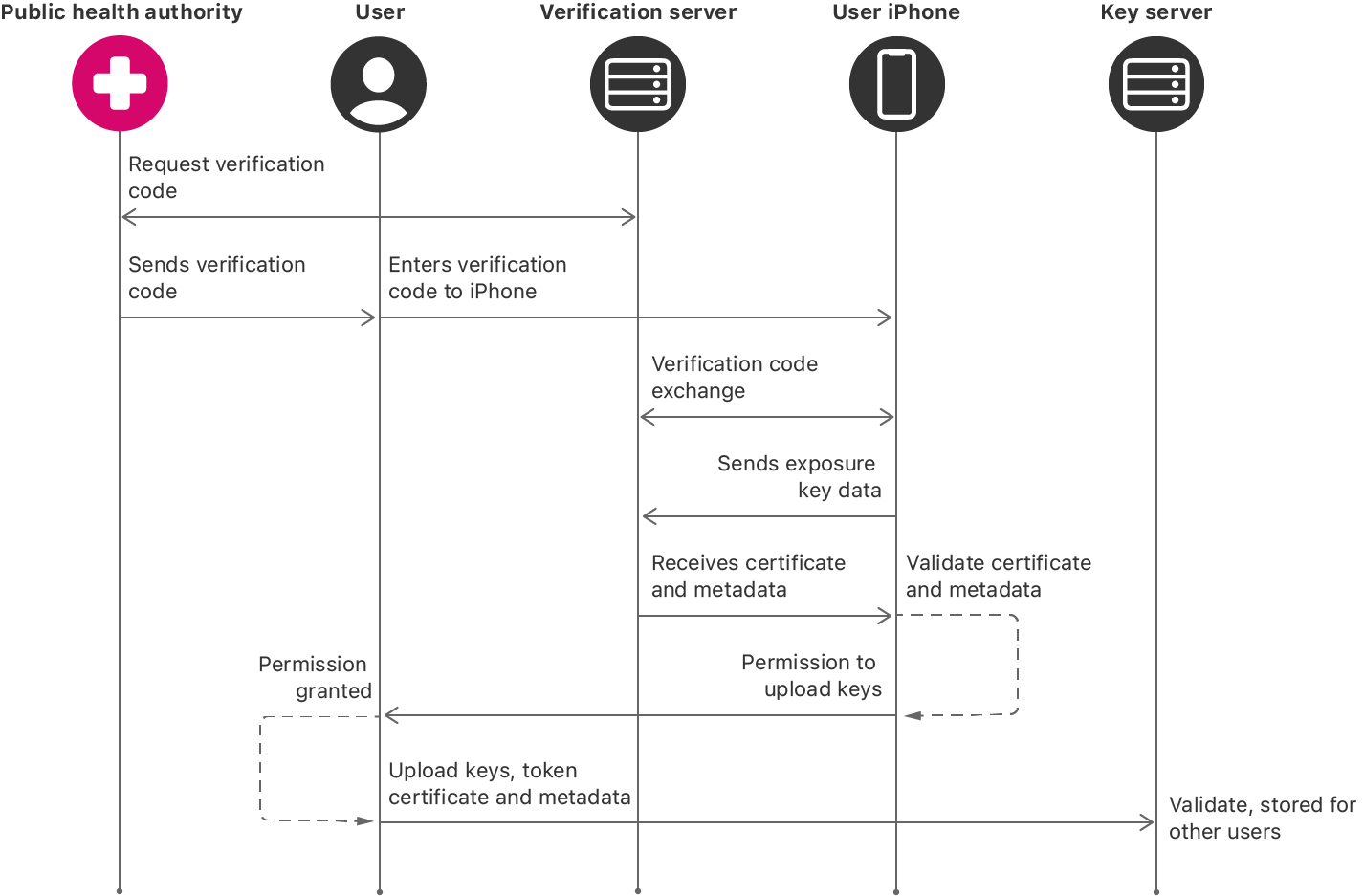

No government or local app integration required. The product shipped “incomplete”, as a set of APIs that left local governments on the hook to write and publish an app. Of course, this was the exact moment in which local governments were swamped with a million coronavirus emergency IT needs. Google and Apple could have more easily run a global unified database that matched anonymous exposures, received an update from users who reported testing positive, and then pushed notifications to everyone, without needing government involvement.

In Apple’s Exposure Notification webpage, it’s front and center that Apple (and Google) don’t want to own any next steps: it’s up to your public health authority to give you further instructions.

In Apple’s Exposure Notification webpage, it’s front and center that Apple (and Google) don’t want to own any next steps: it’s up to your public health authority to give you further instructions.

Even the “lightweight” config-only apps were too difficult for public health groups to rapidly deploy. The folks involved at Google and Apple knew this app requirement would be a big problem. So almost as soon as the feature was launched, a new option emerged called “Notifications Express”.

Unfortunately this is still proved too high a barrier, with the “Express” apps for some localities still delayed for months. The first country to adopt Exposure Notifications, Switzerland, didn’t end up launching until May 25, 2020. Across the US, states varied widely, creating huge swaths of the population with no app for months. California’s app didn’t launch till December. Utah’s launched this week (Feb 16, 2021). We were able to create, test, and approve vaccines faster than offering people the ability to notify other nearby Bluetooth signals that they might have been exposed to covid.

Unfortunately this is still proved too high a barrier, with the “Express” apps for some localities still delayed for months. The first country to adopt Exposure Notifications, Switzerland, didn’t end up launching until May 25, 2020. Across the US, states varied widely, creating huge swaths of the population with no app for months. California’s app didn’t launch till December. Utah’s launched this week (Feb 16, 2021). We were able to create, test, and approve vaccines faster than offering people the ability to notify other nearby Bluetooth signals that they might have been exposed to covid.

The “app store” experience was downright broken for it. How were people to know they could and should download this app to turn this feature on? On day one, users who updated their OS could go to the app store and see a banner that said “Find your location’s exposure notification app”. After clicking on it, and manually selecting a country and state, the app would just say, “no app exists yet for your location”. Nobody got an alert when it finally became available, nobody could opt in to automatically get it when it became available. For a platform that relies on widespread adoption to make the software work, there were way too many barriers to adoption.

What did the government need to do differently?

(This section is focused just on the United States; if you know about other countries and would like to inform me, drop me a note at my first name @ maxcho.com)

It feels at this point like picking on the government for what it needed to differently in the pandemic is beating a dead, desiccated, perhaps even fossilized horse skeleton. But there’s still huge room to better engage with the tech companies.

Tell the tech companies to solve the problem. Public health agencies were clearly unable to rapidly deliver on the app side of this product. If that was knowable in advance (and I suspect it was, if anyone talked to the governments involved), the officials consulted needed to object more vehemently to this expectation, and ask Google and Apple to make it work end to end and lower the burden on locality.

Get the federal government to do it. This is not the kind of product that needs a 50-state-strategy. States should have insisted the feds take it on; it’s crazy to have different apps for states when people are constantly crossing state borders.

Provide air cover. I don’t know what the conversations were internally about what liability or lawsuits would result from various implementation options. But it’s clear “we’re just an API” and leaving the rest to public health departments is one way to reduce liability, and it’s possible to me that Apple and Google were too timid because they felt like governments wouldn’t protect them from massive downside risks. Courageous political leaders here could have bought Apple and Google breathing room to be a little less timid.

What can the public do better next time?

Refuse to accept mediocre products from Apple and Google. Public pressure, and continued attention, have always reshaped priorities for work I’ve seen at big tech companies. Public demands have also helped tech executives find the courage to take a riskier but better path.

Demand more from their government. Six months to create a database and config file? Recruit volunteers. Ship the first janky thing that works.

Give a little more trust in an emergency. Mostly the conversation about this work was “would it work” and “is it private enough”. We now know the harm— millions dead globally, hundreds of thousands in the U.S.— and we should have been willing to take more daring steps as a general populace to try to mitigate that.

This is too important to give up on. Keep polishing.

The next pandemic is right around the corner. More so than ever before, we have the technical tools to treat our immune systems and our borders as crude last lines of defense, and our computers and databases and sensors as the front line to mitigate problems.

Don’t drop the Exposure Notification system. Next year, use it for the flu. Use it for measles. For tuberculosis. And with enough practice, maybe we’ll iron out the kinks, and will be better prepared for the next pandemic.